For over a century, Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity predicted the existence of ripples in the fabric of spacetime, known as gravitational waves. These elusive 'cosmic whispers' were thought to be generated by the most violent events in the universe – colliding black holes, merging neutron stars, or exploding supernovas. Yet, for decades, they remained purely theoretical, a testament to the immense power of Einstein's mind but seemingly beyond the reach of human detection. That all changed on September 14, 2015, when the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made an announcement that sent shockwaves (pun intended) through the scientific community and truly rewrote the textbooks of physics and astronomy.

Introduction to Scientific Discoveries

The universe, long observed primarily through light, revealed a new dimension of perception on September 14, 2015, with the first direct detection of gravitational waves by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). This monumental scientific discovery, announced in early 2016, not only confirmed a century-old prediction of Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity but also inaugurated a revolutionary era of gravitational-wave astronomy. The faint 'chirp' detected by LIGO, emanating from the violent collision of two black holes billions of light-years away, was a cosmic whisper – a sound wave in the fabric of spacetime itself. This event, dubbed GW150914, unequivocally demonstrated the universe communicates not just through light and particles, but also through ripples in the geometry of space and time.

Overview: Listening to the Universe's Deepest Rumbles

For centuries, our cosmic understanding relied almost exclusively on electromagnetic radiation. While invaluable, light leaves vast regions and many extreme events, like black hole mergers, hidden. Gravitational waves, by contrast, pass unimpeded through matter, carrying pristine information directly from their cataclysmic origins. LIGO's detection opened a 'gravitational-wave window,' allowing scientists to observe previously hidden phenomena and test extreme physics. The journey involved decades of unprecedented precision engineering, computational power, and global scientific collaboration, building an instrument sensitive enough to measure changes in distance smaller than one-ten-thousandth the diameter of a proton over four-kilometer arm lengths. LIGO's success fundamentally reshaped our understanding of gravity, spacetime, and the dynamic universe.

Principles & Laws: Einstein, Relativity, and the Fabric of Spacetime

Einstein's General Theory of Relativity

At the core of gravitational wave detection is Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, published in 1915. This theory revolutionized gravity, moving beyond Isaac Newton's force concept. Einstein proposed gravity as a manifestation of spacetime curvature: massive objects warp the fabric of spacetime around them, dictating how other objects and light move. Imagine a bowling ball on a stretched rubber sheet; it creates a depression, and smaller marbles curve towards it, following the distorted surface.

Gravitational Waves: Ripples in Spacetime

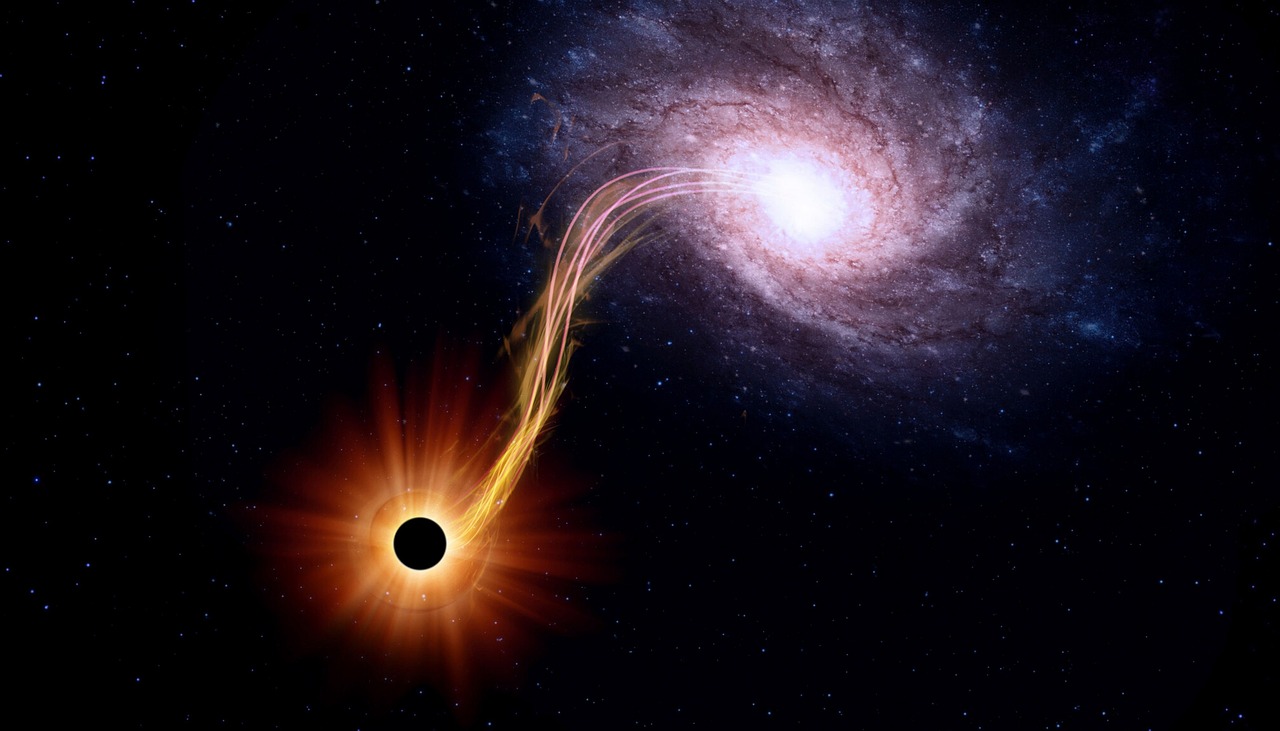

A profound prediction of General Relativity was gravitational waves. Just as accelerating electric charges produce electromagnetic waves, accelerating massive objects should produce gravitational waves – dynamic ripples in spacetime curvature propagating at the speed of light, carrying energy and momentum. Sources powerful enough to create detectable waves are extraordinarily violent: supernovae, rapidly rotating neutron stars, and most notably, the inspiral and merger of binary systems involving black holes or neutron stars.

When a gravitational wave passes, it momentarily stretches space in one direction while compressing it perpendicularly. As the wave continues, the stretching and compressing directions swap. This effect is incredibly tiny, changing distances by less than an atom's width over thousands of kilometers, for all but the most extreme cosmic events.

Methods & Experiments: The Ingenuity of LIGO

The Laser Interferometer Concept

Detecting such minuscule distortions requires instruments of extraordinary sensitivity. LIGO achieves this using laser interferometry. A detector like LIGO is a giant L-shaped instrument with two perpendicular arms, several kilometers long. A laser beam splits, each half travels down an arm, reflects off a mirror, and returns. The two beams then recombine. In the absence of a gravitational wave, arm lengths are equal, and the recombined light interferes destructively (no light reaches the detector).

LIGO's Advanced Design and Detection Mechanism

LIGO comprises two identical observatories, in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington, separated by over 3,000 kilometers. This separation is crucial for distinguishing cosmic signals from local disturbances and for sky localization. When a gravitational wave passes, it differentially alters the arm lengths – stretching one while compressing the other. This minute change means the laser beams travel slightly different distances, arriving out of phase at the recombination point. This phase difference causes constructive interference, producing a tiny flash of light detected by a photodetector.

To enhance sensitivity, LIGO employs several innovative technologies: Fabry-Pérot cavities effectively lengthen the laser's path; high-power lasers and ultra-high vacuum minimize background noise; and sophisticated seismic isolation systems (suspending mirrors like pendulums) reduce environmental disturbances. Quantum squeezing techniques further reduce quantum noise from the laser light, pushing the limits of measurement precision.

Data & Results: Unveiling a Violent Universe

GW150914: The Inaugural Detection

The first direct detection, GW150914, was monumental. On September 14, 2015, both LIGO detectors simultaneously observed a transient gravitational-wave signal. Analysis revealed it originated from the final milliseconds of two stellar-mass black holes merging. One was about 36 solar masses, the other 29. They coalesced into a single 62-solar-mass black hole, radiating about 3 solar masses of energy as gravitational waves – an output momentarily greater than all observable stars combined. The observed signal was a characteristic "chirp," rapidly increasing in frequency and amplitude, precisely matching theoretical predictions for merging binary black holes, a stunning confirmation of General Relativity in the strong-field regime.

Subsequent Detections and Multi-Messenger Astronomy

Since GW150914, LIGO (and Virgo) has detected dozens of gravitational wave events, predominantly from merging binary black holes. These have populated the "black hole family tree" with previously rare masses, challenging stellar evolution models. A truly groundbreaking event was GW170817, detected on August 17, 2017, from two merging neutron stars. Revolutionary was its simultaneous observation across the electromagnetic spectrum: a short gamma-ray burst detected 1.7 seconds after the gravitational wave signal, followed by a "kilonova" remnant. This confirmed neutron star mergers as cosmic factories for heavy elements like gold and platinum, marking the dawn of multi-messenger astronomy.

Applications & Innovations: A New Cosmic Perspective

A New Window on the Universe

Gravitational-wave astronomy provides an entirely new way to study the cosmos, complementing traditional electromagnetic methods. It probes extreme and violent events—like black hole births and neutron star dynamics—and potentially the echoes of the Big Bang, revealing regions of the universe opaque to light, such as supernova interiors or the very early cosmos.

Probing Fundamental Physics and Cosmology

Gravitational wave observations offer unparalleled opportunities to test fundamental physics, probing General Relativity in its most extreme regime. Deviations from Einstein's predictions, if found, would revolutionize our understanding of gravity. These waves also act as 'standard sirens' in cosmology: combining the gravitational wave signal (providing absolute luminosity distance) with electromagnetic observations (providing redshift) allows independent measurements of the universe's expansion rate (Hubble constant), offering a powerful check on other cosmological measurements and potentially resolving current tensions. Study of the gravitational-wave background could also provide insights into the earliest moments of the universe.

Key Figures: Pioneers of Gravitational Wave Astronomy

The achievement of LIGO is a testament to the vision and perseverance of many individuals:

- Albert Einstein: Predicted gravitational waves in 1916 as a consequence of General Relativity, laying the theoretical foundation.

- Rainer Weiss: Conceived the interferometric detection technique in the late 1960s, developing prototypes and conceptual designs for LIGO.

- Kip Thorne: A theoretical astrophysicist who provided critical theoretical guidance for LIGO, helping predict detectable waveforms from merging compact objects.

- Barry Barish: As LIGO's second director from 1997, he transformed the project into a large-scale international collaboration, leading construction and commissioning of the Advanced LIGO detectors.

Weiss, Thorne, and Barish were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2017 for their decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves.

Ethical & Societal Impact: Collaboration, Inspiration, and Open Science

LIGO's success profoundly demonstrates the power of international collaboration, involving over 1,000 scientists from more than 100 institutions across multiple countries. This scale of teamwork, resource sharing, and expertise is a model for 21st-century scientific endeavors. The discovery has captured public imagination, inspiring new generations by showcasing the excitement of fundamental research and fostering deeper appreciation for our universe. Furthermore, commitment to open science, with widely shared data, strengthens the scientific process and accelerates further discoveries.

Current Challenges: Pushing the Boundaries of Detection

Increasing detector sensitivity remains a primary goal, battling various noise sources:

- Quantum Noise: Fundamental noise from light's quantum nature; mitigated by techniques like quantum squeezing.

- Thermal Noise: Vibrations from atoms within mirrors and coatings; explored solutions include cryogenic cooling and advanced materials.

- Seismic Noise: Ground vibrations from natural and human activity; LIGO's elaborate suspension systems minimize this, but it limits lower-frequency detection.

Data analysis presents another challenge: extracting faint signals from noisy data requires sophisticated algorithms and computational power. Improving sky localization is also crucial for enabling rapid follow-up electromagnetic observations.

Future Directions: The Next Generation of Observatories

The future of gravitational-wave astronomy is bright, with plans for more sensitive detectors and new observational windows:

- Third-Generation Ground-Based Detectors: Projects like the Einstein Telescope (Europe) and Cosmic Explorer (USA) aim for significantly longer arms (up to 40 km) and cryogenic technologies, vastly increasing sensitivity and range to probe the entire observable universe and the early cosmos.

- Space-Based Observatories (LISA): The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) will consist of three spacecraft with million-kilometer arms, sensitive to lower-frequency waves. It will detect mergers of supermassive black holes, inspirals of compact objects, and potential signals from the early universe.

- Pulsar Timing Arrays (PTAs): Efforts like NANOGrav use precisely timed pulsars to detect ultra-low-frequency gravitational waves from merging supermassive black hole binaries. Recent evidence suggests a common gravitational-wave background detected by PTAs.

Combining these different detectors, sensitive to various frequency ranges, will provide a pan-spectral view of the gravitational-wave universe.

Conclusion: A New Era of Discovery

LIGO's first detection of gravitational waves marked a pivotal moment in science, affirming one of Einstein's most profound predictions and opening an entirely new channel for cosmic observation. It confirmed binary black hole systems, provided unprecedented tests of General Relativity in extreme environments, and heralded multi-messenger astronomy with GW170817. The 'cosmic whispers' LIGO has begun to decode reveal a universe far more dynamic and violent than imagined. As technology advances and new observatories come online, gravitational-wave astronomy promises to continue rewriting physics, offering deeper insights into elemental origins, galaxy evolution, and the very fabric of spacetime. We are now truly listening to the universe's most profound secrets.