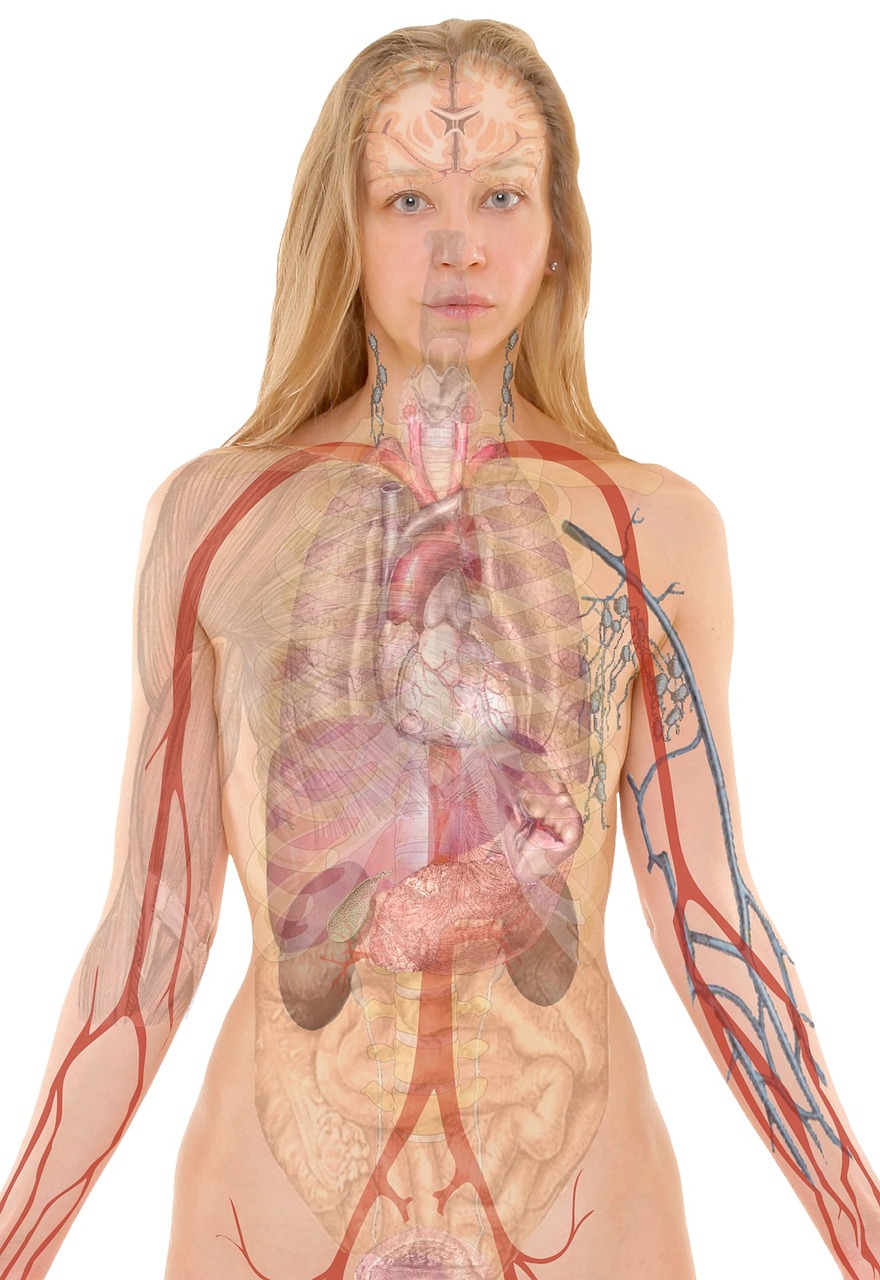

The human brain possesses an extraordinary capacity to learn and remember, a faculty vital for survival and adaptation. However, this same capacity can become a source of profound suffering when memories of traumatic events become entrenched, leading to debilitating conditions like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and severe anxiety disorders. For millions worldwide, these indelible imprints dictate daily life, unresponsive to conventional therapies. But what if we could precisely target and 'rewrite' these painful memories? Enter optogenetics, a groundbreaking neuroscientific technique that promises to unlock the very circuits of fear, offering a beacon of hope for a future free from the grip of trauma.

Introduction to Human Science

Overview

Traumatic memories, often at the core of debilitating conditions such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), phobias, and severe anxiety disorders, represent a significant challenge in mental health. These memories are not merely unpleasant recollections; they are deeply engrained neural representations that can trigger intense emotional and physiological responses, fundamentally altering an individual's quality of life. Current therapeutic approaches, including psychotherapy (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Exposure Therapy) and pharmacotherapy (e.g., SSRIs), offer considerable relief for many, but often fall short for those with severe, refractory symptoms. Limitations include high relapse rates, side effects, and the inability to directly target the underlying pathological neural circuits.

In this context, the advent of optogenetics represents a revolutionary leap forward. Optogenetics is a cutting-edge neuroscience technique that combines genetic engineering and light to precisely control the activity of specific neurons in living tissue. By enabling scientists to turn neurons on or off with millisecond precision, optogenetics offers an unprecedented level of control over brain function. The promise of optogenetics in the realm of traumatic memory lies in its potential to directly manipulate the very neural circuits that encode, store, and retrieve these distressing experiences, offering a pathway to not just manage, but potentially rewrite or erase traumatic memories.

Principles & Laws

The Neurobiology of Fear and Memory

To understand how optogenetics can intervene in traumatic memories, it's crucial to first grasp the intricate neurobiology of fear and memory. Fear memories are primarily processed and stored within a complex network of brain regions, often referred to as the fear circuit. Key players include the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC).

- Amygdala: Often called the brain's 'fear center,' the amygdala, particularly the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and central amygdala (CeA), is critical for the acquisition, storage, and expression of fear. The BLA receives sensory information and projects to the CeA, which in turn orchestrates fear responses like freezing, elevated heart rate, and hormonal release.

- Hippocampus: This structure is vital for forming and retrieving contextual fear memories. It associates the fear-inducing event with the specific environment in which it occurred, allowing for the retrieval of fear even in the absence of the original threat cue.

- Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): The PFC, particularly the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), plays a crucial role in the regulation and extinction of fear. It exerts top-down inhibitory control over the amygdala, helping to dampen fear responses when a threat is no longer present. Dysfunction in these pathways is implicated in the persistence of fear in PTSD.

The formation and modification of these memories rely on synaptic plasticity, specifically long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), mechanisms by which synaptic connections between neurons are strengthened or weakened, respectively.

Memory Reconsolidation Theory

A pivotal development in memory research, the theory of memory reconsolidation, provides a critical window for intervention. Traditionally, memories were thought to be fixed once consolidated. However, pioneering work by researchers like Karim Nader demonstrated that when a consolidated memory is retrieved, it becomes transiently destabilized – a labile state during which it is susceptible to modification. To be restabilized, the memory must undergo a process called reconsolidation, which involves de novo protein synthesis. If this process is blocked or altered during the labile window, the memory can be weakened, strengthened, or updated.

This 'reconsolidation window' (typically minutes to hours after memory retrieval) offers a unique opportunity for therapeutic intervention, allowing for targeted manipulation of traumatic memories without affecting other, unrelated memories.

Optogenetics: A Revolutionary Tool

Optogenetics harnesses genetically encoded light-sensitive proteins, known as opsins, derived from microbes. These opsins, such as Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) for excitation or Halorhodopsin (NpHR) for inhibition, can be expressed in specific neuronal populations using viral vectors. Once expressed, shining light of a specific wavelength onto these neurons (typically via an implanted optical fiber) can precisely control their electrical activity. For example, blue light can activate neurons expressing ChR2, while yellow light can inhibit neurons expressing NpHR.

The power of optogenetics lies in its unparalleled spatiotemporal precision. Unlike pharmacological agents that affect broad brain regions or electrical stimulation that lacks cell-type specificity, optogenetics allows for the manipulation of genetically defined neurons in specific circuits at millisecond timescales. This precision is crucial for dissecting and modulating the intricate, time-sensitive processes involved in fear memory formation and reconsolidation.

Methods & Experiments

Viral Vector Delivery of Opsins

The first step in an optogenetic experiment is the targeted delivery of opsin genes to specific neuronal populations. This is typically achieved using recombinant adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). AAVs are engineered to be replication-deficient and are effective at delivering genes into neurons. The viral construct includes the opsin gene fused to a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) and, crucially, a cell-type-specific promoter. For instance, a CaMKIIa promoter can target excitatory neurons, while a GAD67 or VGAT promoter can target inhibitory interneurons. The AAV is microinjected into the target brain region of an animal model (e.g., rodents), allowing for the expression of the opsin exclusively in the desired cell type within that region.

Animal Models of Traumatic Memory

Most foundational research on traumatic memory and optogenetics is conducted in rodent models, primarily using fear conditioning paradigms. These paradigms reliably induce and allow for the measurement of fear memories:

- Auditory Fear Conditioning: An animal (e.g., a mouse) learns to associate a neutral auditory tone (conditioned stimulus, CS) with an aversive event, such as a mild foot shock (unconditioned stimulus, US). Subsequent presentation of the tone alone elicits a fear response, typically measured as freezing behavior.

- Contextual Fear Conditioning: The animal learns to associate a specific environment (context) with an a foot shock. Later re-exposure to the context alone induces freezing, demonstrating the formation of a contextual fear memory.

These models allow researchers to precisely control the timing of memory formation, retrieval, and reconsolidation, making them ideal for optogenetic interventions.

Targeted Neural Circuit Manipulation

Following opsin expression, optical fibers are surgically implanted into the target brain region, allowing light to be delivered to the neurons expressing the opsin. Experiments are designed to intervene during specific phases of memory processing:

- During Memory Acquisition: Manipulating activity during the learning phase to prevent or alter fear memory formation.

- During Memory Retrieval and Reconsolidation: This is the most promising window for rewriting traumatic memories. After a fear memory is established, it is retrieved by presenting the CS (e.g., the fear-conditioned tone). During the subsequent reconsolidation window, optogenetic stimulation (excitation or inhibition) is applied to specific neurons or circuits. For example, inhibiting basolateral amygdala principal neurons during reconsolidation has been shown to prevent the memory from being restabilized as fearful. Conversely, activating fear-extinction promoting neurons in the mPFC during this window could enhance extinction learning.

- During Extinction Training: Optogenetic activation of specific mPFC pathways or inhibition of amygdala outputs can facilitate the learning of new, non-fearful associations with the CS, thereby strengthening extinction memories.

Researchers utilize sophisticated behavioral rigs, often coupled with video tracking and physiological monitoring, to quantify behavioral outcomes such as freezing, avoidance, and anxiety-like behaviors following optogenetic interventions.

Data & Results

Erasing or Suppressing Fear Memories

Numerous studies in rodents have provided compelling evidence for the ability of optogenetics to modify fear memories. For instance, research has shown that selective inhibition of specific neuronal populations within the amygdala, particularly during the memory reconsolidation phase, can dramatically reduce or even 'erase' learned fear responses. By targeting specific projection pathways – such as those from the basolateral amygdala to the central amygdala – scientists have demonstrated that disrupting this information flow during retrieval can prevent the fear memory from reconsolidating in its original, potent form. Animals subjected to such interventions later show significantly reduced freezing behavior and other fear-related responses when re-exposed to the fear-conditioned stimulus.

Furthermore, activation of specific populations of neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which are known to project to and inhibit the amygdala, has been shown to enhance fear extinction. By bolstering these extinction-promoting circuits with optogenetic stimulation, researchers have successfully promoted the suppression of fear memories, effectively diminishing the behavioral expression of fear without necessarily erasing the original memory trace.

Enhancing Positive Memories (Counterconditioning)

Beyond simply suppressing or erasing negative memories, optogenetics also offers the potential for counterconditioning – that is, strengthening competing, positive or neutral memories to override traumatic ones. Studies have explored activating reward pathways or specific hippocampal circuits during the presentation of cues previously associated with fear. By pairing a previously aversive stimulus with optogenetically induced positive reinforcement, animals can learn new, non-fearful associations, effectively rewriting the emotional valence of the memory. This approach holds significant promise for conditions where the goal is not just to reduce fear, but to rebuild a healthy relationship with previously traumatic triggers.

Circuit-Specific Modulation

One of the most profound achievements of optogenetics is its ability to demonstrate that the precise manipulation of specific neural circuits, not just entire brain regions, yields distinct behavioral outcomes. For example, researchers have shown that activating or inhibiting different populations of inhibitory interneurons within the amygdala can have opposing effects on fear expression. Similarly, manipulating the inputs from the hippocampus to the amygdala, as opposed to inputs from the prefrontal cortex, can differentially affect contextual versus cue-specific fear memories. This level of granular control underscores the potential for highly targeted therapeutic interventions, moving beyond the blunt tools of previous generations of brain research.

Applications & Innovations

Therapeutic Potential for PTSD

The ultimate goal of this research is to translate these findings into effective treatments for human conditions like PTSD. Optogenetic interventions, if successfully adapted for human use, could offer a fundamentally new approach to PTSD therapy. Instead of merely managing symptoms or teaching coping mechanisms, these techniques could directly target the pathological neural signatures of traumatic memories. By selectively weakening or updating the maladaptive fear associations during the reconsolidation window, optogenetics could potentially diminish the emotional impact of the trauma, thereby reducing flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors. This approach aims for a more enduring and transformative change than current therapies alone.

Broader Implications for Anxiety Disorders

The principles learned from PTSD research extend to a wide range of anxiety disorders. Phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder are all characterized by maladaptive fear responses to specific cues or situations. Optogenetics could be used to:

- Treat Specific Phobias: By directly intervening in the fear circuits associated with the phobic stimulus during reconsolidation, reducing the associated panic and avoidance.

- Manage Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Potentially by modulating chronic overactivity in fear-generating circuits or enhancing inhibitory control from the prefrontal cortex.

- Address Panic Disorder: By targeting neural pathways involved in interoceptive fear and the misinterpretation of bodily sensations as threats.

Combination Therapies

It is highly probable that future optogenetic-inspired treatments will not be standalone therapies but will be integrated with existing psychological and pharmacological interventions. Imagine a scenario where a carefully timed optogenetic intervention could open a 'window of plasticity' in the brain, making an individual more receptive to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or exposure therapy. By temporarily reducing the potency of a traumatic memory, optogenetics could allow patients to engage more effectively with therapeutic exercises that were previously too overwhelming. This synergistic approach could amplify the efficacy of current treatments, leading to more robust and long-lasting recovery.

Key Figures

The field of optogenetics and memory research stands on the shoulders of giants. A central figure is Karl Deisseroth, a psychiatrist and bioengineer at Stanford University, whose lab pioneered the development and widespread application of optogenetics, revolutionizing neuroscience research. His work, alongside that of Edward Boyden, transformed the ability to control neural activity with unprecedented precision.

Fundamental contributions to our understanding of memory reconsolidation and fear circuits came from researchers like Joseph LeDoux (New York University), whose extensive work mapped the amygdala's role in fear, and Karim Nader (McGill University), who famously demonstrated the lability of retrieved memories, establishing the reconsolidation theory as a cornerstone of memory research. Other influential figures include Roger Nicoll (UCSF) for his work on synaptic plasticity, and many other researchers globally who have applied these techniques to dissect and manipulate specific neural circuits involved in memory, learning, and emotion.

Ethical & Societal Impact

Identity and Memory Manipulation

The ability to intentionally alter memories, particularly traumatic ones, raises profound ethical questions about personal identity. Our memories fundamentally shape who we are – our experiences, our understanding of the world, and our sense of self. If traumatic memories are significantly altered or erased, does it change the essence of the individual? Is it possible to selectively remove the 'bad' without inadvertently affecting the 'good' or the lessons learned? The concept of authenticity and the potential for a 'sanitized' past require careful consideration.

Safety and Informed Consent

Translating invasive techniques like optogenetics to human therapy brings forth significant safety concerns. The use of viral vectors, brain implants, and chronic light stimulation demands rigorous long-term safety studies. Furthermore, the complex nature of brain function means that unintended side effects or alterations to other cognitive processes must be thoroughly investigated. The ethical challenges of informed consent in such novel, powerful, and potentially irreversible interventions are immense, particularly when dealing with vulnerable populations suffering from severe mental illness.

Access and Equity

Advanced neurotechnologies are often expensive and require specialized expertise, potentially leading to issues of access and equity. If optogenetic therapies prove highly effective, will they be available only to a privileged few? Ensuring equitable access to such transformative treatments will be a critical societal challenge, preventing the creation of a two-tiered system of mental healthcare.

Current Challenges

Translation to Human Therapeutics

The most significant hurdle is translating promising rodent research to human application. The invasiveness of current optogenetic methods – requiring viral gene delivery and implanted optical fibers – presents considerable risks and ethical concerns for routine clinical use in humans. While gene therapy for neurological disorders is progressing, the widespread application of direct brain circuit manipulation for psychiatric conditions is still distant. Non-invasive or minimally invasive alternatives are highly sought after.

Specificity and Off-Target Effects

Despite its precision, applying optogenetics to the complex human brain introduces challenges. The human brain contains billions of neurons, and ensuring that opsin expression and light delivery are perfectly confined to the desired subpopulation of neurons in the target circuit, without affecting adjacent, functionally distinct neurons or pathways, remains a technical challenge. Unintended 'off-target' effects, even subtle ones, could have unpredictable consequences on mood, cognition, or behavior.

Sustained Efficacy and Long-Term Stability

Even if memories are successfully modified, questions remain about the long-term stability of these changes. Will the fear responses return over time (relapse)? Are the underlying neural circuits truly 'rewired' in a permanent way, or do compensatory mechanisms in the brain eventually restore the traumatic memory? Long-term follow-up studies are crucial to assess the durability of optogenetic interventions and ensure they provide lasting relief.

Future Directions

Non-Invasive or Minimally Invasive Approaches

Future research is heavily focused on developing less invasive methods for neuromodulation that retain optogenetic-like precision. This includes exploring:

- Chemo-optogenetics (DREADDs): Using engineered receptors activated by otherwise inert synthetic ligands, offering a less invasive pharmacological control over genetically targeted cells.

- Ultrasound or Magnetic Stimulation: Harnessing focused ultrasound or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) guided by insights from optogenetics to non-invasively target specific deep brain regions with greater precision.

- Viral Vector Advancements: Developing safer, more efficient, and more specific viral vectors, possibly delivered systemically or intranasally, that can cross the blood-brain barrier and target neurons with high fidelity.

Enhanced Precision and Cell-Type Specificity

The refinement of genetic tools will continue to be a priority. This includes developing new opsins with varied light sensitivities and kinetics, as well as increasingly sophisticated promoter systems and 'intersectional' genetic strategies that allow for the targeting of highly specific cell populations based on the co-expression of multiple genes. The goal is to isolate and manipulate only the exact neurons contributing to pathological memory, leaving adjacent circuits untouched.

Closed-Loop Systems and Personalized Medicine

A significant future direction involves the development of closed-loop brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). These systems could monitor brain activity in real-time, detect pathological neural signatures associated with traumatic memory retrieval or impending flashbacks, and then automatically trigger precise neuromodulatory interventions. This 'on-demand' or 'as-needed' intervention would represent a highly personalized medicine approach, tailored to individual brain states and potentially offering a dynamic way to manage the re-emergence of traumatic symptoms.

Conclusion

Optogenetic interventions in fear circuits represent one of the most exciting and rapidly advancing frontiers in neuroscience and mental health. The unparalleled precision of optogenetics has provided invaluable insights into the fundamental mechanisms of fear memory formation, storage, and retrieval. From the ability to erase specific fear memories in animal models to the potential for counterconditioning and enhancing fear extinction, the scientific promise is immense.

While significant challenges remain, particularly in translating these invasive techniques to safe and ethical human therapeutics, the knowledge gained from optogenetic research is already informing the development of next-generation, less invasive neuromodulation strategies. The long-term vision is a future where the debilitating grip of traumatic memories can be safely and effectively loosened, offering profound relief to millions suffering from PTSD and other anxiety disorders, ultimately improving human well-being through the precise manipulation of the brain's most intricate circuitry. The journey is complex, but the destination—a deeper understanding and mastery over the very architecture of our fears—is worth every ethical and scientific consideration.